The Time Machine

The Time Machine has always been one of my favorite all-time movies--that is, the original version. Especially the scene where its inventor, George, enters his full-size machine, carefully inserts a masterfully crafted lever, excitedly yet slowly pushes it forward engaging its intricate mechanisms, and fully immersed in cautious wonderment, watches his surroundings and a store's mannequin across from his residence materially change in appearance season after season, year after year. I would have loved to place that same time machine on Church Street directly across from the building that became the

Dock Street Theater so I could have watched the comings and goings through its many remarkable changing and passing years.

Today, standing on Church Street and looking directly towards the storied

Dock Street Theater, the eye catching wrought iron balcony and sandstone columns gracing its facade immediately captures your imagination. The theater is by far Charleston's most remembered, not because it was the City's only theater, but simply because its appellation has survived Charleston's tumultuous history of confrontation, conflagration, and cataclysm. Its cycle of existence reminds me of the Bible passage at Revelation 17:8, which in part reads, "...and they that dwell on the earth shall wonder...when they behold the beast that was, and is not, and yet is." The

Dock Street Theater opened on February 12, 1736--"was", went out of existence in the Great Fire of 1740 and was replaced with the Planter's Hotel--"and is not", and finally returned as the

Dock Street Theater on November 26, 1937--"and yet is."

During the time the

Dock Street Theater was not, hidden in the shadows of time and lesser known by most people today, there existed two celebrated theaters housed in architecturally impressive structures. The

Broad Street Theatre, also called

Charleston Theatre, was built at the corner of Broad Street and Middleton Street (now New Street).

The New Theater was constructed on Meeting Street.

The

Broad Street Theatre was designed by James Hoban (best known as the architect of the White House in Washington). The masonry playhouse was built by contractor Capt. Anthony Toomer. As reported by the City Gazette on August 14, 1792, "the ground was laid off for the new theatre, on Savage's Green. …125 feet in length, the width 56 feet, the height 37 feet, with a handsome pediment, stone ornaments, a large flight of stone steps, and a palisaded courtyard. The front will be on Broad Street, and the pit entrance on Middleton Street. Owned by West and Bignall, the theater seated 1,200 people. It opened February 1793.

Soon after the

Broad Street Theatre opened, Santo Domingan refugee John Sollée built a French-language theater on Church Street. Competition between the two theaters was fierce, and heightened by conflicting political alliances after France declared war on Great Britain in February 1793. While the wealthy elite patronized Shakespearean productions on Broad Street, supporters of the Jacobin revolutionaries flocked to the comedies, acrobatics, and light opera presented at the French Theater. After the 1795-96 season, it was effectively out of business.

While the

Broad Street Theatre remained closed, the French and English theater companies merged during the spring of 1796 and through the summer of that year performed at a Church Street theater under the name of "

City Theatre." Then, in the spring of 1800, the parties cooperated to open both playhouses. The re-opened Broad Street venue would present drama and the Church Street venue music, acrobatics, and ballet. Sollée then renovated his Church Street property as a music hall and ballroom, known for years as "

Concert Hall." After 1800, the Broad Street theater was Charleston's only playhouse, and generally referred to as

The Theatre.

The theater closed when the War of 1812 broke out, reopening in the autumn of 1815 under the management of English actor Joseph Holman. Junius Brutus Booth performed two engagements in the winter of 1821-22. On February 20, 1826, the City Gazette advised its readers that a "New Portico" would be erected at the expense of Mrs. Gilbert to induce attendance. Within a few years, the portico had been added to the Broad Street facade.

|

| Broad Street Theatre became Medical College in 1833 |

By 1832, attendance had fallen off sharply. The decline was attributed to the steep price of tickets at a time when many had "circumscribed means." The tight wallets were a response to Charleston's weak economy, and the theater soon closed permanently. On July 25, 1833, the

Broad Street Theatre was purchased by the faculty of the Medical College of the State of South Carolina for the sum of $12,000. The building was destroyed in the great fire of December 1861.

With the closing of the Broad Street theater, the city was without a proper theatrical venue. In early 1835, a group of businessmen led by Robert Witherspoon agreed to develop a new theater enterprise. They bought a lot on Meeting Street from the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free Masons of South Carolina, and organized "The Charleston

New Theatre," as a joint-stock company.

|

| New Theatre |

Famous architect, Charles Reichardt (designer of the Charleston City Hall, original Charleston Hotel, Chisolm House, and Millford Plantation), designed the world-class auditorium. It was erected by a partnership of builders, Curtis, Fogartie and Sutton. While construction was underway, the theater was leased to an experienced actor-manager who brought a company of players to Charleston.

The Charleston Courier, December 18, 1837 described the 1200-seat

New Theatre as being two full stories in height above a raised basement. The stuccoed brick building had a massive Ionic portico, with four columns, above an arcaded base. The portico was accessible only from within the building; entry from Meeting Street was through the arcade level. Three main doors opened to the lobby/vestibule, which had a ticket office at one side, ladies withdrawing room at the other, and a corridor leading to the boxes and seating floor. Above the richly ornamented auditorium was a large dome, at its center a forty-eight lamp chandelier eight feet across.

The

New Theatre opened on December 15, 1837 to a large audience. After Mr. Latham delivered a "poetical address" written for the occasion by William Gilmore Simms, theater manager William Abbott took the lead role in the play,

The Honey Moon, supported by Miss Melton and Mrs. Herbert, who also sang an "afterpiece."

In March of 1838, Junius Booth was booked to make his first appearance in Charleston in more than a decade at the theater. His characterization of Sir Giles Overreach was declared by the Southern Patriot as being on the whole "the most thrilling piece of acting we have ever seen…" In May, 1840, the celebrated German ballerina Fanny Elssler, whose appearances in Baltimore and New York had caused riots among her adoring fans, danced at Charleston's theater.

Although Abbott left Charleston in 1841, a series of managers were relatively successful in running the theater for the next twenty years. In 1858 and 1859, Edwin Booth (son of Junius Booth and brother of John Wilkes Booth) played several engagements. He reenacted his father's great roles as Richelieu, Hamlet, Giles Overreach, and Othello. The

New Theatre was also destroyed in the great fire of December 1861.

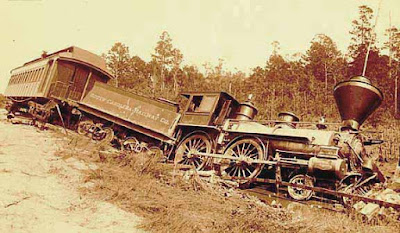

|

| The steps in the foreground was all that was left of the New Theatre after the 1861 fire and the Civil War. |

The

Broad Street Theatre and the

New Theatre were not the only venues in Charleston back in their day just as the

Dock Street Theatre is not the only one today, but they were prominent venues with impressive structures. What set the

Dock Street Theatre apart from all others? It was America's first built exclusively to be used for theatrical performances and its name has prevailed over the ravages of time. It seats 475 people with state-of-the-art lighting and sound.

Not far from the

Dock Street Theatre on Queen Street is the

The Footlight Players. It was formally organized and incorporated in 1932. In 1934, the group purchased an old 1850 cotton warehouse that eventually became their permanent home. There are many other smaller venues located throughout Charleston--all producing quality entertainment.

French is considered to be "le langage de l'amour." So, one may ask: What is it about French that qualifies it to be called "the language of love?" One reason, French is very euphonious. The tone of the spoken words tend to be more delicate sounding to the ears. Also, vowels and consonants are well distributed resulting in more harmonious phrases. Finally, the need to conjugate verbs makes it ideal for writing poetry and music.

French is considered to be "le langage de l'amour." So, one may ask: What is it about French that qualifies it to be called "the language of love?" One reason, French is very euphonious. The tone of the spoken words tend to be more delicate sounding to the ears. Also, vowels and consonants are well distributed resulting in more harmonious phrases. Finally, the need to conjugate verbs makes it ideal for writing poetry and music.